Came the day I found myself in the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, in Baltimore, Maryland.

Back up.

Months ago, I built an intricate scale model of a crime scene.

Back up further.

In 2020, as my mother was in her final days, I needed a way to fill the endless time after she was no longer conscious. When I was both alert for, and dreading, her final breath. I began researching the Hinterkaifeck case- an unsolved murder from 1922. And I have never stopped.

Back up further.

Ten years ago, I came across some images online of tiny scenes called the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death. They were built by Frances Glessner Lee, a complicated woman who stubborned her way into a world that wanted desperately to deny her an education, a profession, a life. She’s colloquially known as the mother of American forensic science. She engaged in a research-based making practice that produced spectacularly detailed, and painfully human, scale models of death scenes.

Go forward a little.

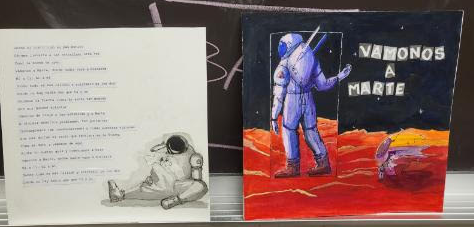

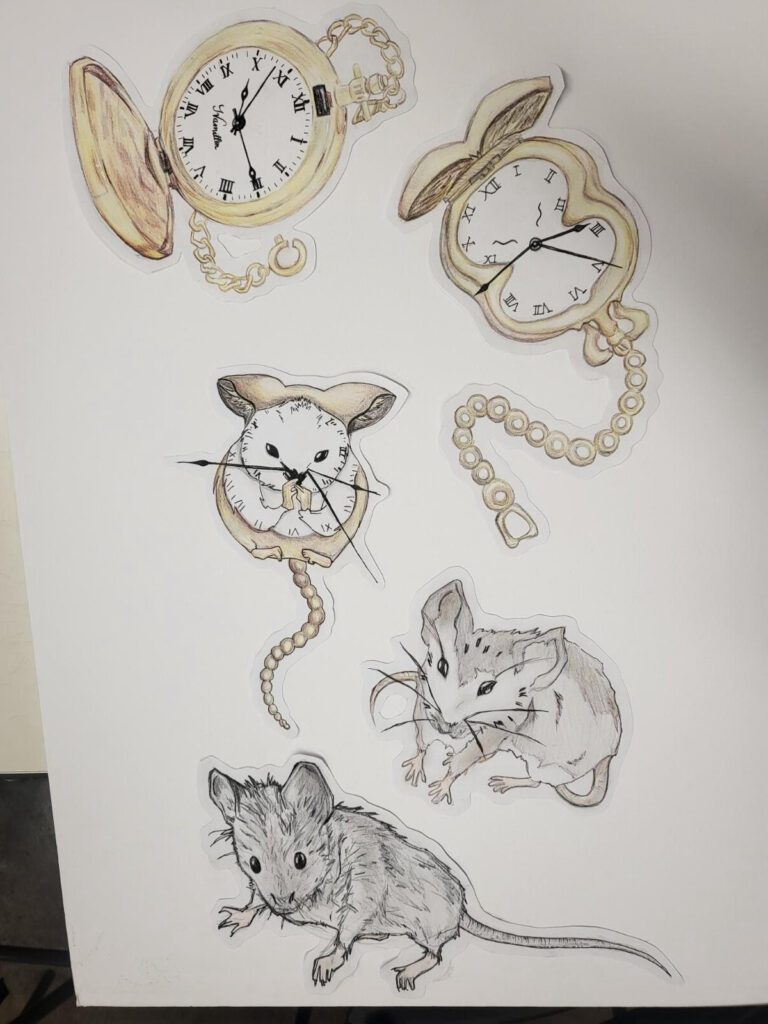

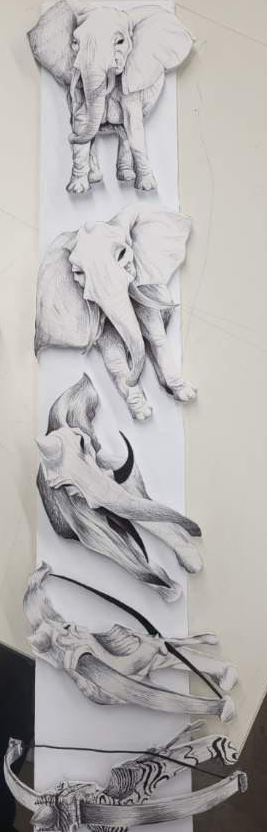

In 2015, I began teaching my art students about the Nutshells. They’d choose an unsolved case, research it, and build a scale model of the scene. Some were good. Many were just okay. But some were spectacular.

In 2017 I began building life-sized installation art pieces which dealt with missing people; the missing missing, as Kenna Quinet calls them. The folks dismissed by officialdom because of race, profession, or addiction. Those deemed less missing, and less missed. There’s a clear genealogical line to this work from the Nutshells- they were never far out of mind.

Finally, in 2022, I built my first version of a Nutshell. It came out of that research into Hinterkaifeck, begun when I was desperate to feel something- anything- other than the anticipation of grief. And it came when I got to a point where I was floundering in the research, and needed a way to break through to some kind of understanding. The model allows me to see the spaces in which the Gruber family lived, and died- and how the confines of their home affected their deaths.

I’m part of a community online, a group comprised mostly of women who are interested in unsolved crimes. It is, you may be surprised to learn, one of the kindest and most supportive places on the internet. I thought they’d be interested in what I’d made, so I posted images and video of my model there.

This led to a conversation with a person who turned out to be the expert on Frances Glessner Lee and her work. Bruce Goldfarb is the curator of the Nutshells- he oversees their care, and guards their secrets, at the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME) in Baltimore. He’s also the author of 18 Tiny Deaths, the definitive biography of Frances Glessner Lee and her work.

Goldfarb invited me to see the Nutshells. Which is how I found myself, in the hot wet summer of 2022, standing in a small back room at the OCME, stunned into incoherence by the objects surrounding me.

Goldfarb understands these objects, and their maker, better than anyone living. And he guards them well. No secrets will be revealed. Before we meet, Goldfarb warns me that people can’t resist trying to solve the nutshells. I try to keep this in mind while moving between them, getting caught in them. But he’s right; they’re irresistible. It’s impossible to look away from them as stories. As puzzles to be solved.

I find myself occupying a layered subject position, standing in this strange room full of strange rooms. I’m watching my partner, who has no interest in crime or forensics or even in art, really, but who has come along because it’s an adventure, and he’s nothing if not supportive. He’s entranced. He’s maybe slightly terrorized. I’m also watching myself watch him- and at the same time, being pulled into the space of the Nutshells. I’m viewer, voyeur, participant. The Nutshells’ space expands and consumes everything, and everyone, around them.

Everyone wants a clean narrative. Introduction, rising action, climax, denouement. You won’t get that from the Nutshells. They’re moments in time, caught in the aftermath of something- an event, a series of actions that led to an accident, or a murder. What you see is what’s left; you have to try to reconstruct the story from the scene in front of you here and now. Glessner Lee built the ending. You have to find the beginning.

Goldfarb opens the cabinet containing “Pink Bathroom.” It has its own secret: through the window of the bathroom, you can see a slice of wall, and a hint of a fire escape. Just enough to know that this bathroom is in an urban environment, that there are (or should be) neighbors all around. Once the cabinet is opened, the rest of the scene is revealed- an air shaft, with windows. The fire escape extends up and down.

None of this was meant to be seen. But it’s there. And it says something about Glessner Lee’s craftsmanship, and her obsessive intensity. It would have been easier not to build that air shaft. Glessner Lee was thorough- but she only shows us what we need to see. There’s just enough information to discover the truth- if we know what to look for, and how to interpret what we find.

True crime people (I hesitate to call us “fans,” which implies a species of admiration, or spectatorship, which I find distasteful) talk about “going down the rabbit hole”- a process in which a case captures your imagination, takes you hostage. You begin digging, relentlessly looking for more information, any tiny clue, that could solve the puzzle. What did that rope mean? Why was that towel there? Where was the final bullet casing? Wherever you are- eating breakfast, sitting through a faculty meeting, walking the dog- your brain is in the case, among its warrens and endless turnings.

Each Nutshell is a rabbit hole in itself. It contains worlds- perhaps made more compelling because they are so delicately empathetic. The figures are dolls- fragile toys, playthings for children. Recontextualized into depictions of adults, whose lives are over. The stories aren’t true, but they feel true, because the people in them look like us. They’re fictions, but they have names. They have professions. They are often (not always) depicted in their own domestic spaces. The spaces where they should be safe.

Images within images. I become weirdly convinced that Glessner Lee played a game with the images contained in the Nutshells. The paintings on the walls, the printed calendars, are all trying to tell us something. In one Nutshell, a painting of a fox is displayed. A fox in the henhouse? Nothing in art is accidental (though Glessner Lee did not consider herself an artist; it’s difficult to find another language with which to describe her constructions). Everything is a choice. Every detail of a wound, of the wallpaper, of the most prosaic things which make up a life. And which are left behind.

I am immeasurably moved by one figure’s shoes. He’s depicted in two spaces- another double consciousness- on the ground outside a saloon and later, in a jail cell. He’s a laborer. Even if you couldn’t tell by his clothes, and his lunchbox, you could tell by his shoes- the soles are worn down. You can see the shine of deliberate scuffing- the result of wearing down the tiny soles so that these shoes which have never known pavement will tell us something about the figure wearing them.

I can’t get enough. I am consumed. But eventually we have to walk back into the world.

In the rental car, on the way back to our DC hotel, I am overwhelmed. Exhausted by looking. I fall asleep, into that immediate REM abyss, and don’t wake until we’re pulling into the garage. I’ve lost time. My head is still back in the shabby-genteel confines of Dark Bathroom. It’s a space I recognize- a once-grand home, sectioned off into apartments- and an object to admire. And I’m haunted by it- not in any supernatural way, but in the way Avery Gordon describes haunting:

“…not a case of dead or missing persons sui generis but of the ghost as a social figure. It is often a case of inarticulate experiences, of symptoms and screen memories, of spiraling affects, of more than one story at a time…it is a case of modernity’s violence and wounds, and a case of the haunting reminder of the complex social relations in which we live.”

What Glesnner Lee built were spaces in which the dead do not speak, but their environments function as their ghosts. Their residues. Here is the book someone left open on the coffee table, because they expected to pick it back up. There is the table, set for a breakfast no one will ever make. We are left in the dissonance between the world as it is, and the world they expected to be.

What follows is a 1:24 scale model of the Hinterkaifeck farm, where the entire Gruber-Gabriel family, and their maid Maria Baumgartner, were murdered between March 31 and April 4, 1922. The case remains unsolved.

For the past several years, I’ve been studying and writing about the Hinterkaifeck case. In order to better understand the scene, I consulted floorplan sketches made by police and witnesses, the Gruber family’s probate records, and the few surviving photos of the farmhouse. However, flat images and lists have limits; they can’t give a sense of scale, of space, or tell you much about how people might move through a structure. And so, the scale model was born. I’ve found it incredibly useful in understanding not only the life of the Hinterkaifeck farm, but also its inhabitants and their daily realities.

The scale model comes from an assignment I give my art students. They’re expected to do research on a historical mystery, and recreate the scene in either 1:12 or 1:24 scale. This is based on Frances Glessner Lee’s forensic artworks/investigative tools: the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death.

Anita S Wooten Gallery

Valencia College

Orlando, FL

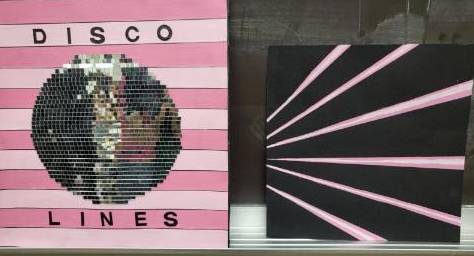

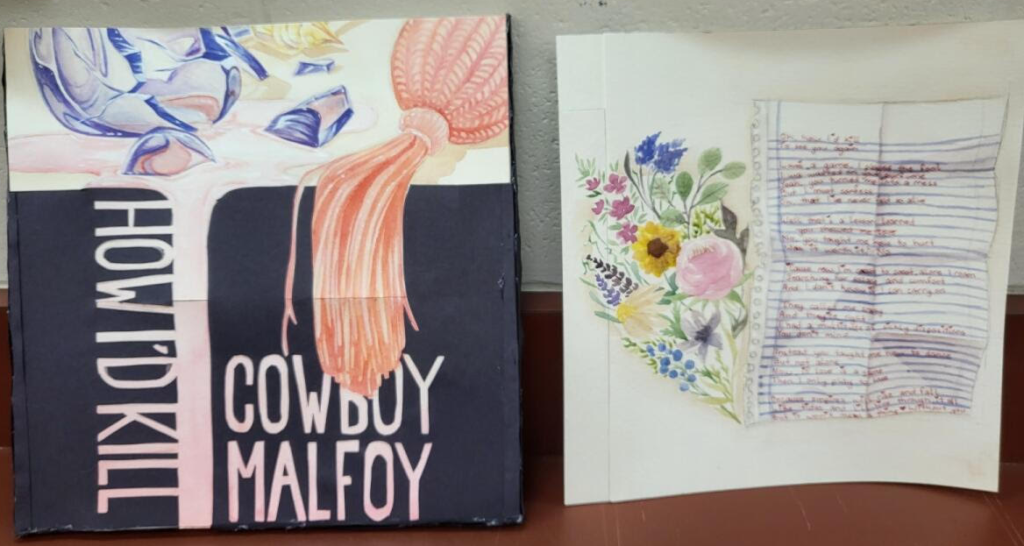

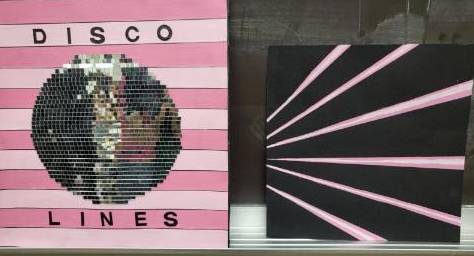

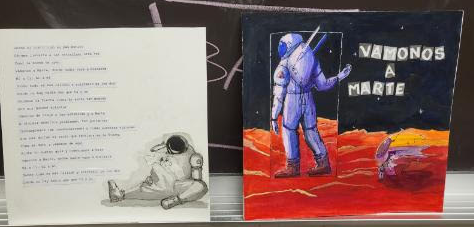

It Goes With the Couch

June 15-August8, 2023

Co-curated with Rachael Zur

Artworks by Xuanlin Ye, Jamie Nakagawa Boley, Jenny Chernansky, Bill Wells, and Ben Creech

Earth and Water, Wind and Fire: Ceramics by Hadi Abbas

January 12-March 3, 2023

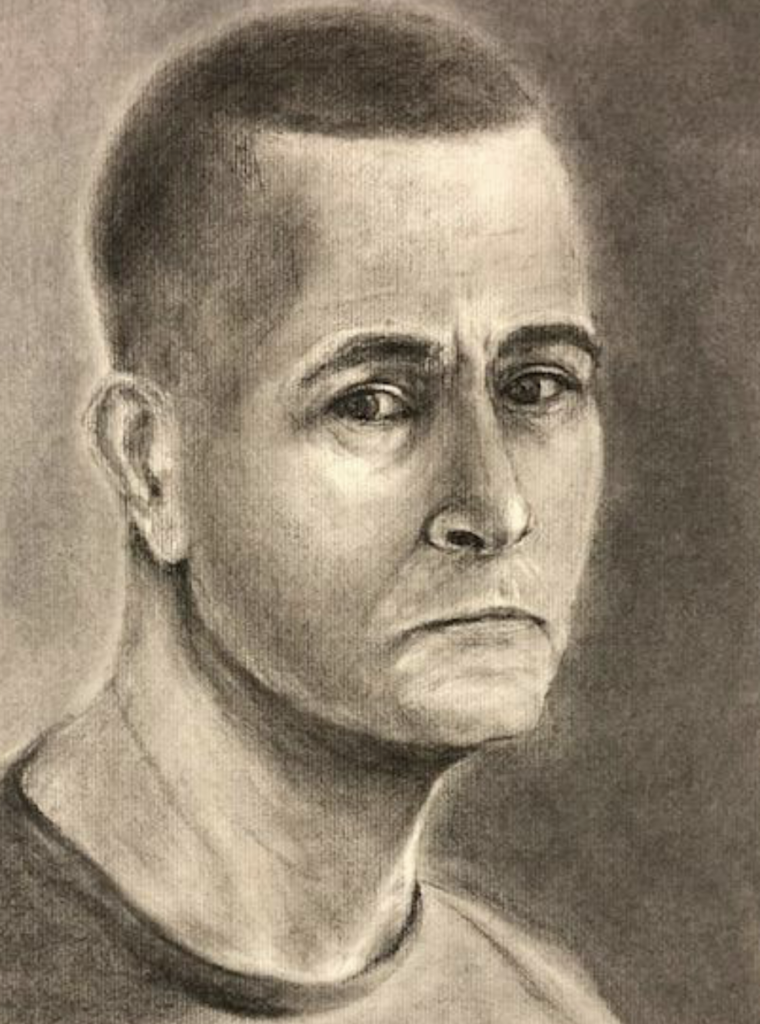

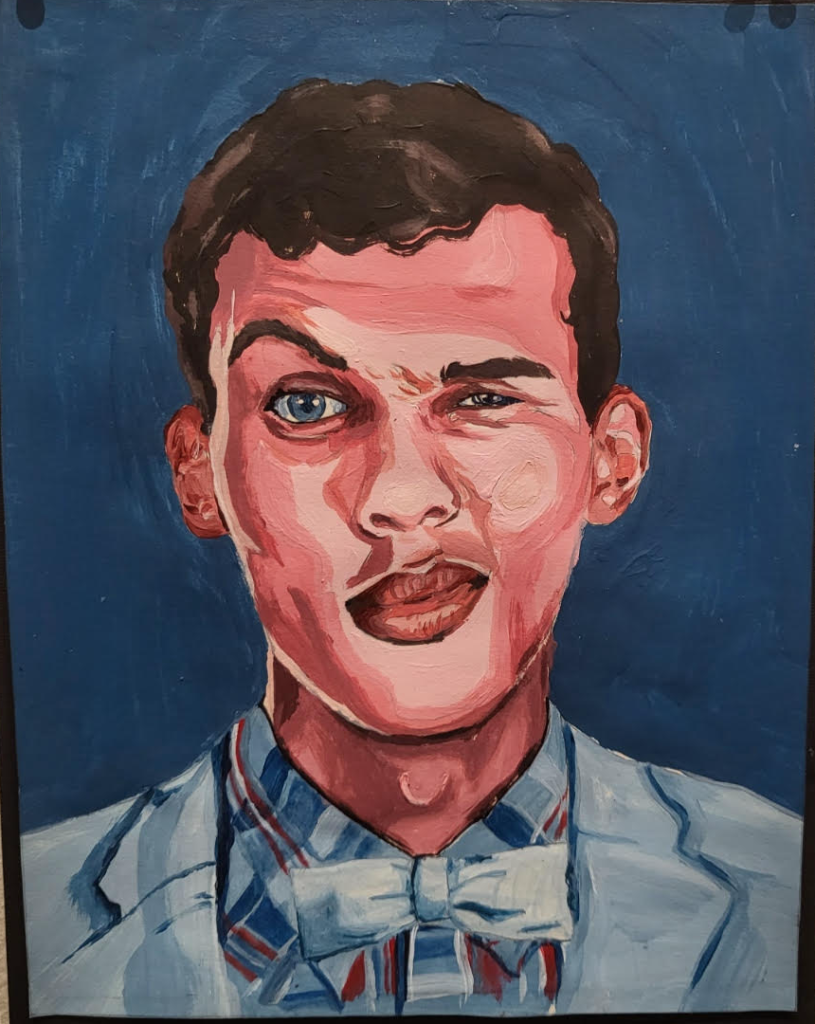

Selected Fine Arts Faculty 2022

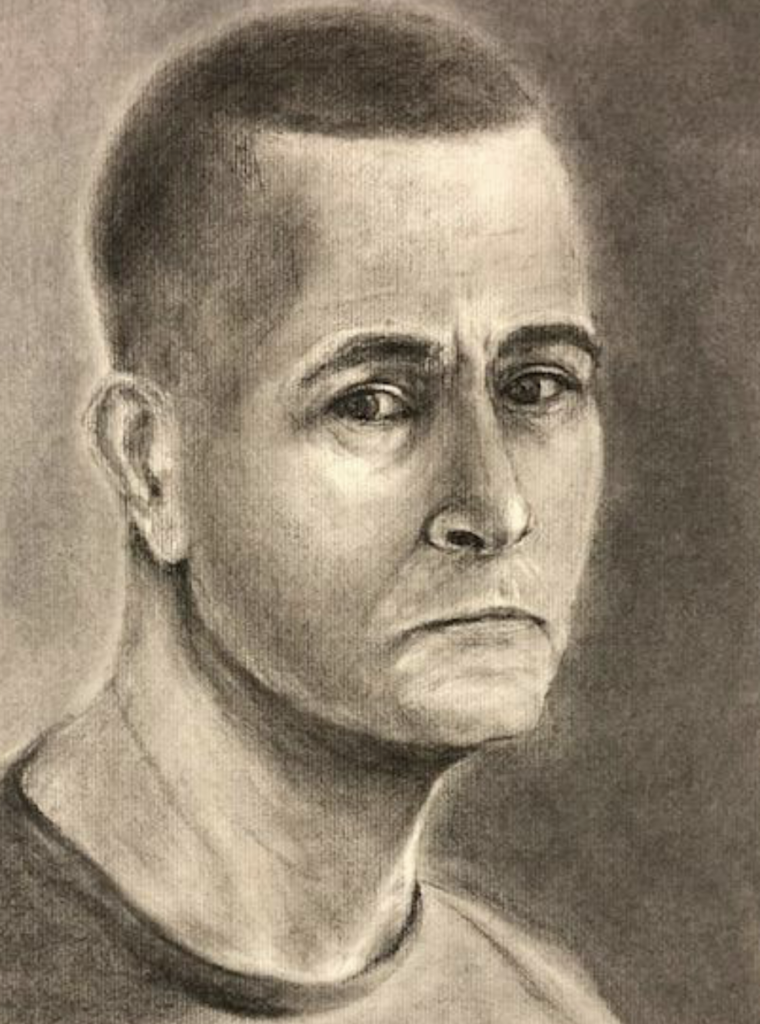

KYLE

Michael Galletta

Richard Munster

Rose Casterline

Leah Sandler

Cassandra Anselmo

CS Frank

Viktoriya McGrath

David Cumbie

Marcus Barrett

Haris Ahmad

Dino Casterline

Dennis Schmalstig

Dennis Angel

Camillo Velasquez

Kathleen Marquis

November 3-December 9, 2022

Affliction: Photographs by Natalie Diienno and Nika de Carlo

September 8-October 14, 2022

Co-curated by Jacob Rodriguez

Natalie Dienno: Through the Blue Hour, Self Portrait (MRI/Hunch), 2018

Natalie Dienno: Through the Blue Hour, Self Portrait (MRI/Hunch), 2018

Nika de Carlo: Fifth Anniversary, 2019

Standing in the Gap of the Here and In Between

Jamie Nakagawa Boley

September 3, 2020 – October 9, 2020

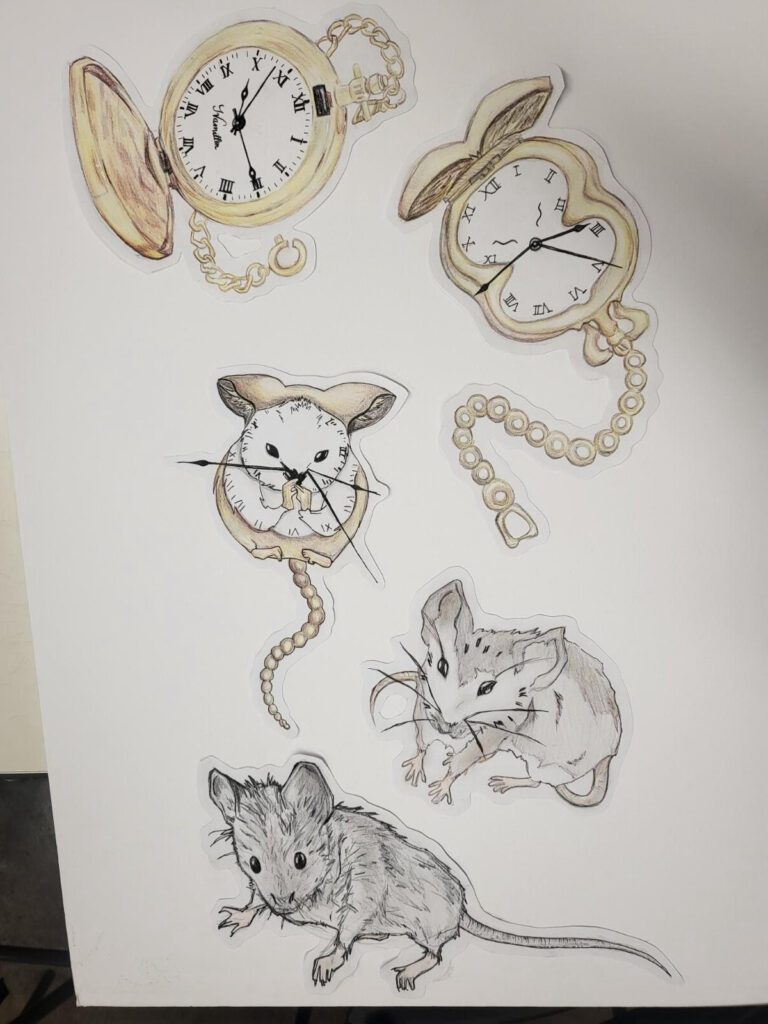

Tattoo Me!

Faun Manne

January 14, 2021 – March 4, 2021

Continue reading Curatorial Work

Continue reading Curatorial Work

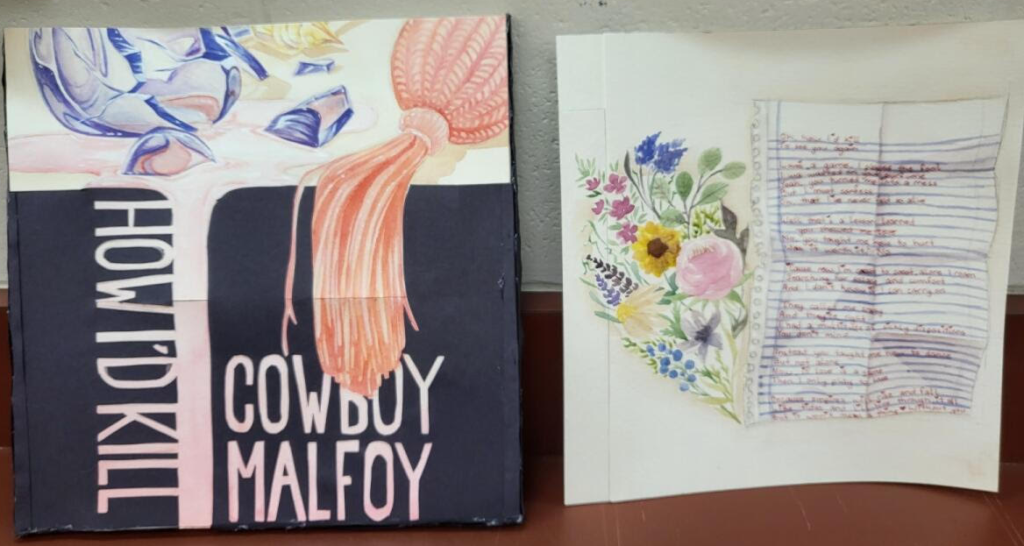

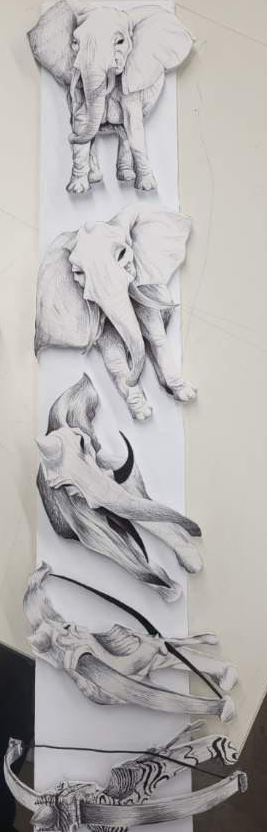

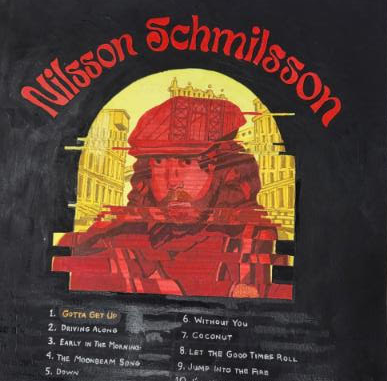

Each semester, I ask my students to construct dioramas in the style of Frances Glessner Lee’s Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death.

This means reckoning with the body- in or out of its context, left behind, dumped, the object of violence. In these cases, bodies provide the narrative, bodies are the narrative.

And, often, the stories bodies tell are ambiguous- clearly, something violent happened to them, but the story remains a riddle; the circumstances muddied by the elements, and by time.

Often, the bodies in question are missing- out of sight but still central, still holding the power to fascinate. In all cases, the dioramas are about ways of seeing the (in)visible body. They’re about seeking information, using image as a way to construct a narrative that suits the visible evidence and makes sense in its own context. They’re not about solving the mystery- about closure, whatever that means. Rather, they’re about learning to look, learning to read the body in its context as text, to reconstruct the circumstances of its unmaking.

No image, for reasons that will become obvious.

I am the faculty advisor for my college’s Art Club. The students and I have been working on a mural project all semester- an ambitious piece that covers an entire first floor hallway, where the offices of Arts and English faculty are located. The work involves a lot of contortions- twistings of the body, stretching, strange yoga poses. We end up sore, tired, sloppy with paint at least two days a week. We are often also subjects of fun and observation; Admissions staff will come through with prospective students, to show us off.

My students taught me something on Monday, though I’m not yet sure how to articulate it. We had been working for around half an hour. And then, the lights went down. The entire neighborhood was plunged into darkness. I sat back and stretched, ready to call it a day. But my students simply took out their smartphones, turned on the flashlight devices built into them, and kept painting.

Valencia College, School of Arts and Entertainment

2019-present

Drawing I

3D Design II

2D Design I

Spring 2019

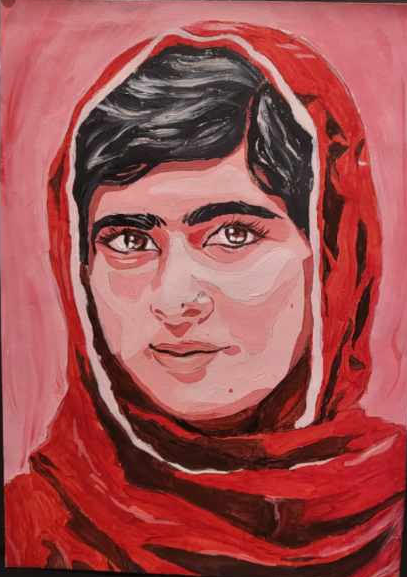

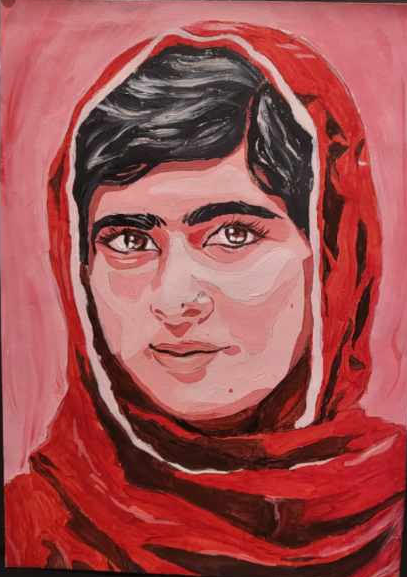

First Year Seminar II: Heroes and Villains

Throughout history, we have looked to cultural heroes and villains to define and describe who we are, what we value, and what it means to be human.

This course examines the presentation of glorified and vilified figures throughout history, in order to understand the ways in which hero/villain narratives are used to shape opinion, reinforce political/social agenda, and construct meaning.

In this course, students will build on the skills learned in FYS I in order to conduct meaningful research and construct clear, thesis-driven writing. Students will learn to examine primary and secondary sources of biographical/historical information for argument, bias, and reliability. Students will learn and apply appropriate research methods and ethics to their own work, to read critically and deeply, to examine information for context as well as content, and to present their own research in objective language, with appropriate citations and attributions.

2013-2019

Drawing I

An experiential learning course in drawing for the general education student as well as art majors, students learn the fundamentals of drawing realistically from life, including drawing edges, spaces, relationships, values, and color. Students will draw the traditional subjects of still life, landscape, and the portrait working with both linear and mass drawing materials.

Drawing II

This course in drawing is designed for art majors as well as the interested and passionate novice. This course builds on and refines the experience of Drawing I, focusing on a variety of tonal and color media, and emphasizing the line. The course begins with formal concerns, and moves toward explorations in invention and abstraction. The course includes vocabulary development, critical analysis activities and references to historical models of drawing and the evolution of drawing, which will include figure drawing and life studies.

Introduction to Visual Arts

This course teaches students how to understand and appreciate the visual arts, including drawings, prints, paintings, sculptures, and photographs. Students learn to approach visual art from the perspective of the world in which it was created, the artist who created it, the viewer who responds to it, and the object itself. Students learn to identify the formal elements of visual art works, to articulate their art experiences, and to bring to bear cultural and biographical knowledge on their visual art experience.

Art History

This course surveys the history of visual arts from pre-history to the present day. Through a close examination of individual works of art, students learn the artists, the art movements, and the art theories that have guided the creation of art in Western culture from the ancient world to the present. Students develop their ability to look at individual works of visual art with an informed, analytical, and practiced eye and write about art with intelligence and sensitivity. Students will visit the Art Institute of Chicago during the term.

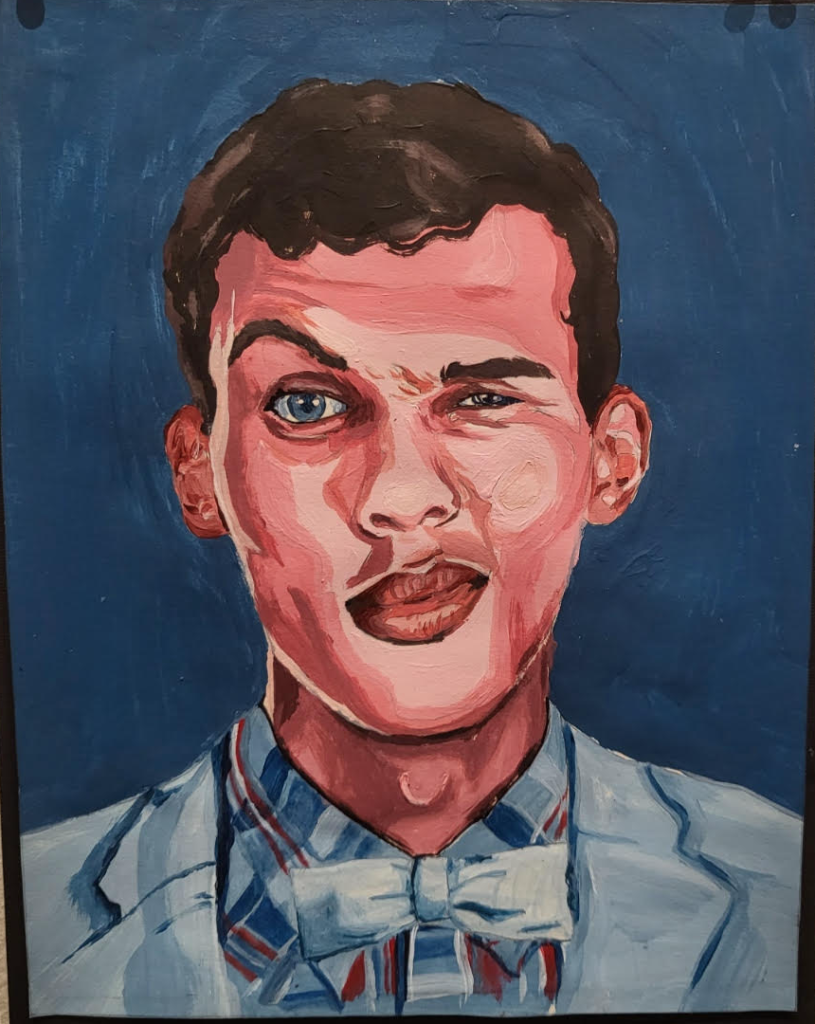

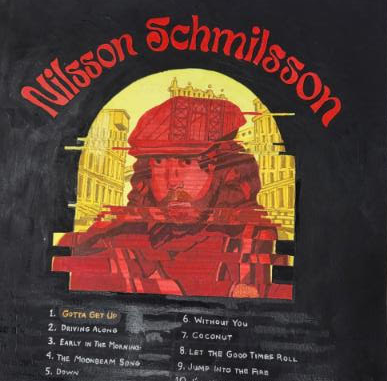

Painting

This course teaches students the knowledge and skills need to paint realistically in both oils and acrylics. Students acquire the basics of color theory, learning how to choose a limited palette, to see color as value, and to develop a harmonious color schemes. Students learn to build paintings on a foundation of solid drawing, attending to content, composition and color to express their ideas in visual form. Through increasingly difficult painting projects, students practice the demands of painting the still life, the landscape, and the human figure.

Painting: Seminar

In this monthly two-hour session, Digital and Studio Arts majors are expected to gather to critique new work, and once per term, to prepare new work for the purpose of evaluation. At these sessions, all of the ARTS faculty and majors will attend giving the benefit of the variety of faculty and peer perspectives on individual works of art and current trends in art and culture. Majors take this course each term they are enrolled in the program.

Topics in Painting

This practicum capstone course extends from the disciplined studio arts practice. Assigned a campus studio and guided by assigned advisors, students reflect on their general education and their courses in the major, create a professional-level portfolio, and produce and display summative art project.

English Composition

In this course students learn the concepts and skills needed to write an effective, college-level expository essay. Through both traditional and workshop methods, students gain greater control over the writing process, essay organization, paragraph construction, and sentence grammar. The course introduces students to the active reading and summary writing skills needed in English 104. Before successfully completing the course, students must demonstrate basic competency in a portfolio of semester writing.

Academic Reading and Writing

This course teaches students the concepts and skills needed to read and write with sources. Students learn how to find, read, summarize, and respond to a variety of college level texts. It teaches students print and electronic search techniques, analytic and synthetic reading skills, and the conventions of academic argument, culminating in ten pages of source-based writing.

The Literary Experience

Using classic and contemporary short stories and poems, this course introduces students to the elements of fiction and poetry and to the interpretive skills necessary to deepen their experience of great literature. Students study both Western literary classics and minority challenges to that tradition, examining the role of stories and poems in a meaningful life.

Honors English Composition

In this course students learn the concepts and skills needed to write an effective, college-level expository essay. Through both traditional and workshop methods, students gain greater control over the writing process, essay organization, paragraph construction, and sentence grammar.

The Honors Learning Community:

A World Beyond the Classroom

Honors Seminar (co-instructor)

ISS Study Abroad: Italy 2015 (co-instructor)

ISS Study Abroad: Spain 2016 (co-instructor)

ISS Study Abroad: England and Scotland 2017 (co-instructor)

ISS Study Abroad: Italy 2018 (co-instructor)

ISS Study Abroad: Greece and Malta 2019 (co-instructor)

In their junior year HLC students will receive an expenses paid international trip designed to engage them in the world beyond the classroom. Past destinations included London, Paris, Rome, Madrid, New York City and Washington D.C. These trips prepare HLC students to take their place in the world by teaching them cultural awareness, respect for individual differences, and giving them first-hand knowledge of the best our culture has to offer.

Foundations of Western Culture

This course introduces students to the major artistic and intellectual movements in our culture. The course introduces the arc of history though the humanities, tracing the foundation of Western civilization from the earliest Judeo-Christian tradition, through the Greco-Roman period, Medieval Europe, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, and the Romantic era, to the age of globalization. The course provides an introductory framework for the Calumet College core curriculum.

Honors Foundations of Western Culture

This course is a historical introduction to the humanities — the subjects that explore what it means to be human: philosophy, literature, painting, architecture, history, religion, music and the performing arts. We will study the great cultural achievements of Western Civilization, how they have developed from the ancient Greeks to the modern world, how they fit into their original cultural context, and how they fit into ours. We will look at great paintings, read classic stories and poems, debate philosophical issues, reflect on sacred texts, and listen to groundbreaking works of music — all in the hope of gaining greater insight into what it means to be alive in the here and now, and particularly what it means to be alive AND free to pursue humanity in its fullest expression.

IST 499 Integrative Project

Under the supervision of the Program Director and another faculty member from an appropriate discipline, the student engages in an integrative project requiring (1) either a written research or reflective paper, or a multimedia program with a descriptive essay, and (2) an oral presentation about the purpose, key points and learning outcomes of project. This course is normally taken in the student’s final semester of study.

PACE College Preparation and Survival

PACE is designed for the incoming student who needs extra support on preparing for college-level reading, writing, and time-management strategies. PACE is designed to foster a sense of confidence through building competence and comfort in the college environment.

Life Experience Assessment Program (LEAP)

Students can earn credit for college-level knowledge and skills they have acquired through a variety of life experiences. A maximum of 30 semester hours of credit can be awarded through the Life Experience Assessment Program. Students must submit a life experience (LEAP) portfolio documenting their life experiences as they relate to college level courses. In order to qualify for this credit option, a student must have earned 12 credit hours, including a college-level English course.

Summer Reading Bridge (co-instructor)

This writing course prepares the student for college-level English by teaching the composition of grammatically correct sentences, well-organized paragraphs and longer papers, while focusing on the syntactical, grammatical and mechanical issues (e.g., prepositions, verbal phrases) common for ESL students. At the end of the course, the instructor will recommend the student registers for ENGL 095, 096, or 103. Not applicable toward a degree.